Profile: Adharshila Learning Center

Wednesday, December, 12, 12 § 5 Comments

From the heart of India, a pedagogy that attempts to balance college fantasies with the reality of a subsistence-farming life.

Place: Madhya Pradesh, India. Located in the center of the country, this vast, largely rural state is home to some 75 million, of which 20% are members of one of the area’s many indigenous groups.

The Skinny: Founded in 1998 by two social activists, the curriculum was designed to “inculcate Adivasi [indigenous] children with a value for learning and an awareness of important issues facing their community.” The school currently has about 100 students, from grade 1-8, 70% boys. Most of the students come from nearby communities and live at the school. The students participate in the operation of the school, ranging from taking care of the school’s cows and organic farm, to cooking and cleaning. The school is an evolving experiment, changing in response to children’s interests and staff skill level. The teaching methods range from traditional classroom teaching, to self-paced worksheets, to project-based learning.

What Matters: The school’s project-based curriculum allows the children to develop the basic skills tested on standardized exams while also producing valuable knowledge related to the history and positive transformation and conservation of their indigenous communities.

More info: http://adharshilask.tripod.com/

http://adharshilalearningcentre.blogspot.in/

And an excellent film within a film made by the kids: http://youtu.be/mXohjGP8byA

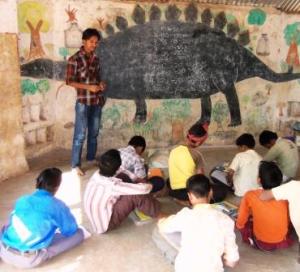

The Adharshila Learning Center was formed with the support of a local Adivasi organization and the surrounding communities. Land was donated, and parents contributed labor and materials to help build the initial structures. The school was founded on a barren, rocky landscape, but twelve years later it sits amidst the shade of numerous groves of trees and a productive farm. Their farm provides an example of organically managed land that produces as much or more than the land of their neighbors, whose traditional farming techniques have been replaced by the use of pesticides and fertilizers. The school itself is composed of a number of interesting structures that make up classrooms, dormitories, libraries, and offices. Some of the buildings are shaped as pentagons or hexagons, and the black boards like dinosaurs. Doors swing above lines on the floor that mark out 30, 45, and 60 degrees.

Afternoon crafts.

Very little at the school appears to be the result of a preconceived master plan, but rather the spontaneous emergence of ideas by teachers or students. However, the school today probably looks much more like a traditional school than either Amit or Jayashree had envisioned when their experiment first began with 35 children and no curriculum. The first two years they primarily focused on the children’s interests. After the first several years they began receiving pressure from parents to prepare the students for the national exams for the 5th certificate, which is needed to gain access and privileges in the civic sector, including getting a driver’s license. Thus began the slow movement towards a more standardized curriculum. Behind the parents’ demands for standardized testing lay the false hope that passing these exams would open doors to good paying jobs in the modern economy. However, coming from rural communities, being a minority ethnicity, and competing against the millions of other job seekers are all daunting hurdles. The ability to pass an examination does not ensure that the children will be equipped with skills and outlooks that could serve them in their future livelihoods—especially when the majority of the children will not enter the “modern economy,” but spend the rest of their lives as farmers in their home villages.

Despite the demand to prepare kids to pass national examinations[1], the school has managed to hold on to some of its founders’ original intent and implement a meaningful learning environment through project-based learning. Many aspects of their curriculum are addressed through investigations on their farm (where topics in biology, geology, and math are easily highlighted), and each year the students engage in some type of community research project. Over the years they have recorded histories of the land where the school is located, and have investigated the erosion of traditional livelihoods, quantifying the loss of seed diversity and organic farming practices, and the increased reliance on money. The project cycle spans many weeks, as the children disperse into the surrounding villages to spend time interviewing community members and analyzing and presenting their findings, sometimes in the form of books or magazines.

The children’s activism does not stop with their project-based research, but also takes the form of drama and writing. They have shown an aptitude and passion for acting, creating their own small theater company. They have performed in many of the local communities, often choosing to focus on difficult social issues, such as alcoholism or domestic violence. They even had an international debut when the World Social Forum was held in Mumbai. The children brought down the house, making the national papers with their drama on the social consequences of harmful World Bank and IMF policies.

Many Adharshila students will not fulfill their parents’ dreams. They must overcome tremendous odds to pass a series of outrageously competitive national examinations, land a spot in a university, and then secure a well-paying job in an urban area. Indeed, most will return to their local communities and work the earth, as their families have done for generations—but they will do so with a much more holistic set of skills that can help them positively transform their local realities. They have pride and understanding of their rich local histories and traditions, organic farming skills to counter the destructive use of fertilizer and pesticides, a developed appreciation of the arts, and a nuanced and quantitative understanding of how various political and market processes have been destroying their environment and culture.

That said, it’s worth noting that there are a number of first wave graduates enrolled in several universities, most with aspirations to find socially conscious work. And the experiments in education at Adharshila are still evolving, trying to find that balance between meeting the unrealistic and inappropriate expectations embodied in the standardized curricula, and creating an authentic learning environment.

-Christian Casillas / Based on November, 2012 Visit

Really wonderful. I think a grassroots (overused word at times) approach makes their lives more real and accessible and college can be about the class system but at best they can bring another kind of qualifying for further educational options through another door. Be great if it changed and the kids in this program could do portfolios of projects they do and are doing to live, and just know how to present and document their work and social media for their work rather then the tests….potentially there is a surge of another kind of learning that demanded the system change to meet that then the kids have to deal with an already unrealistic situation and they can develop more fluidity. I wonder who will sustain in the world order we have in front of us college graduates that are not adapted to what most people have to survive in there or these young people? I think the Dalai Lama said one of the first things he built was the theater up at Dharmsala and then the meditation hall and the hospital because he said keeping that creative culture alive was the glue and being able to change emotions so that they did not run you in the skill of acting helped us to live in another way inside ourselves. I loved the story of the theater for social change in this piece and admire their efforts to create an authentic learning environment.

Thanks for the reply Nanda – i just visited another organization which will provide some insights into a ‘university’ that focuses on portfolio presentation and supports it learners to pursue their passions while thinking critically about our current paradigm of development. I will describe the organization in a future post. Coincidentally, while in McCleod Ganj (the dalai llamas home in exile) we saw a very powerful play by some young people depicting the tragedies occuring in the chinese occupation of tibet. Though it was done in Tibetan – it still had a powerful impact on us. We also visited a Tibetan Children’s Village school (http://www.tcv.org.in/) which is one of the a group of schools started by the dalai llamas oldest sister when they first came to india, with the goal creating a supportive family enviornment as well as providing a curriculum that based more strongly on tibetan language/culture. – Christian

Fascinating story, Christian. The point about how many of the students will go back to their traditional agrarian lifestyle gave me pause. While for much of my life I assumed that the failure of a student to go on to higher education is invariably a deficit in a system, having a son complete his higher education and then work the land, at least for some time, has made me rethink that. Is it advantageous to a society to have all its brightest students go to higher education and professional positions? Or is that an exclusively western, capitalist concept that stems from the glorification of individual accumulation of wealth as the highest form of success? Agriculture is vital to life; does it help a society to have all its bright students funneled into white collar positions, when they could be innovating and modeling techniques for producing food? And with all the impacts of climate change creeping up on us, isn’t innovation in food production likely to become our highest priority? Just some random, half-baked thoughts you’ve sparked. — Paul

Hi Paul, thanks for the comment (and your three excellent prior blog posts). I’m suspect that funneling the best and brightest into agricultural research systems in our current university systems – designed to support a growth model of economy – would by like trying to put out a fire with gasoline. The results of the first green revolution produced more food, but also increased erosion of traditional (aka organic) farming methods, destroyed traditional livelihoods and increased dependance on debt-based financial systems, and increased environmental destruction via a mechanistic form of scientific inquiry that resulted in pesticide/fertilizer based system of agriculture. The destructive nature of this farming system was perfectly described over a hundred years ago by Marx – where he described the ‘metabolic rift’ created by a growing urban population dependent on a centralized, massive food production system, in which nutrients are imported to the farm systems, food are exported to cities, and waste is then deposited. A linear system of resource flow, versus the closed loop system of production, consumption, and ‘waste’ that occurs on any traditional farm. Not to say that increased research and development and experimentation aren’t required, but they need to cone from a much more sustainable economic model, and more holistic model of analysis. In terms of hi-tech – the teachers and kids at Adharshila weren’t organic farmers, but are figuring it out as they go, and after half a decade are producing more than their neighbors who are farming with pesticides and fertilizers. I’m carrying Fukoyama’s One-straw revolution around with me – which I think describes how nature can be our best and simplest teachers for sustainable agriculture. I haven’t read it yet… Christian

I’m curious about thoughts from your oldest son 😉

[…] First published on School Reformed […]